Latest story

The Big Move

On Thursday morning, October 16th, 2014, the old Confederation Heights Campus (CHC) was buzzing with activity as CSE employees were busy filling, sealing, and tagging black crates at their workstations. From favourite pens to Funko Pops, from file folder to footwear, everything had to be accounted for. It was move day.

Excitement had been building for the move to the new Long Term Accommodation (LTA) at 1929 Ogilvie Road for a long time, and CSE had been preparing for the big day for well over a year. Leaving the CHC had its share of challenges. The small, cramped hallways made moving large amounts of materiel and equipment difficult. A small army of students had to be hired to digitize decades’ worth of paper documents, and staff found some surprising things behind furniture that hadn’t been moved in years.

Among the “hidden treasures” found by move coordinators were lost paycheques from the 1980s, a Canadian flag stashed behind a ceiling tile, a mountain of discarded office supplies, a few wayward mice, and an entire Dasco filing cabinet filled with rotting food (it’s possible those last two were connected).

CSE was also determined that the move would be as green as possible, and to that end the Diversion Centre Initiative was established to divert as much as possible away from landfill. By the end of the final wave, CSE had succeeded in diverting 75% of all waste materials that were generated as a result of this move. In total, 306,737 kilograms of material were either reused or recycled.

Security of CSE assets and safety of employees were the main priorities throughout. When employees sealed the two (and no more than two!) moving boxes they had been given, a director would inspect and then seal each one, ensuring they were tagged properly for delivery and could not be tampered with. Individual travel routes for each moving truck and van were set only immediately prior to moving out, and each truck stayed in direct contact with move coordinators via walkie-talkie.

Not a single box was misplaced or lost throughout the entire move.

Overall, the move was a resounding success and employees quickly settled into their new home.

Today, we continue this warm welcoming tradition by inviting co-op students and new hires attend information sessions and tours that guide them through one of Ottawa’s best places to work.

Previous stories

CSE’s Many Homes: SLT and Confederation Heights

This is the fifth part in a multi-part series of historical articles about CSE’s many homes. The buildings that have housed CSE reflected the organization itself: ever bigger, more complex, more effective, and strangely unique. If you missed the previous parts, you can find them below.

CBNRC’s first purpose-built building was located at Confederation Heights, in the middle of undeveloped farmland known as Billings’ Bridge.

The Sir Leonard Tilley Building, or “SLT,” would have modern security features, including movement detection, ultrasonic alarms, a secure internal phone network, a centralized security control room and improved entry systems. By special arrangement with the city (due to pollution concerns), an industrial incinerator was installed for classified waste. Encircling the whole facility was a barbed-wire-topped, sensor-monitored fence with a concrete foundation deep enough to prevent tunneling.

The SLT welcomed its occupants in June 1961 and that space served CSE well for 20 years. Inside, however, it was constantly being redesigned, reapportioned, and upgraded. The greatest drivers of change were to be population, which held steady for many years but then began to rise in the 80s, and technology.

Desktop terminals, previously found only in the technical units, began appearing in analytical and administrative sections beginning in the 1970s. Whole wing floors were eventually required to house the new mainframes, supercomputers, and server rooms. At the same time, maturing COMSEC standards required automated key-generation and manufacturing facilities.

To find new space, CSE started annexing existing nearby properties. It took the small Insurance Building (IB) across Heron Road, various floors in the Billings Bridge Tower (BBT), and off-site warehouse space. It also built new facilities, starting with a one-floor, octagonal reception, and meeting space at the front door.

Eventually, CSE added an entirely new wing, connected at the basement and first-floor levels to the rest of SLT. The new 5-floor building was mostly windowless and encased with electrical shielding to prevent unwanted emissions. “C wing” opened in 1992.

Even that space was insufficient. By the end of the 1990s, CSE had also acquired the former CBC headquarters that sat on a hill across a train track, east of SLT. After extensive renovation, the building opened to staff at the beginning of 2000. The top floor contained executive offices and meeting spaces. Most of the other floors were IT Security offices, labs, and Corporate Services.

The building was named after the late Edward Drake, the organization’s first Director, whose family attended the naming ceremony.

CSE’s Many Homes, Part 4 – The Rideau Annex

This is the fourth part in a multi-part series of historical articles about CSE’s many homes. The buildings that have housed CSE reflected the organization itself: ever bigger, more complex, more effective, and strangely unique. If you missed the previous parts, you can find them below.

By 1950 the CBNRC had grown from a few dozen personnel to almost two hundred. At the same time an ever-increasing suite of machinery was needed to support the mission.

To provide the space, the NRC leased a building on the newly renamed Alta Vista Drive from its owners, The Sisters of Charity of Montreal, known as the Grey Nuns. The four-storey block east of the city had been built in 1915 as a novitiate but was converted into a military hospital as WWII began. The utilitarian, rectangular structure stood in the middle of a field, but was close enough to downtown that the Peace Tower on Parliament Hill was visible from the front door.

Initially, CBNRC was to occupy only three floors at the “Rideau Annex”; the fourth was to be used for storage. As would so often happen, requirements overtook planning. The fourth floor was renovated and given to a 24/7 communications centre shortly after the building was occupied in the winter of 1949/50.

Staff who worked at “The Farm”, as it was informally known, remember the environment outside as initially quite rural. Cows grazed in nearby fields and wild grass fires occasionally burned up to the property boundary. A bus shuttled employees from downtown Ottawa in the morning and returned them in the afternoon. Inside, the building was poorly ventilated: the air was choked with tobacco smoke during the winter and unbearably hot in the summer. The windows were kept open for ventilation, but this meant that a gust of wind would send papers flying.

The collegiality that had characterized the organization since the war continued at the new location. At lunch there was volleyball behind the building, croquet in front, table tennis inside, and an occasional flying disc tossed from the top floor.

Ultimately, the Branch’s stay at the Annex was short-lived. The antiquated architecture could not support the increasingly technical organization, and there simply wasn’t enough room. By 1958 work was underway on a replacement in the city’s south end. CBNRC moved out in 1961. The building was soon demolished and replaced in the mid-60s with the apartment block that remains on the site today.

CSE’s Many Homes, Part 3 – The LaSalle Academy

This is the third part in a multi-part series of historical articles about CSE’s many homes. The buildings that have housed CSE reflected the organization itself: ever bigger, more complex, more effective, and strangely unique. If you missed Parts 1 and 2, you can find them below.

On the day after Labour Day in 1946, Canada’s permanent cryptologic agency began work as the Communications Branch of the National Research Council (CBNRC). In charge was LCol Edward Drake (Ret’d), the country’s standout cryptologic leader during the recently concluded Second World War.

The few dozen employees who reported to work on that September morning were members of the military’s Joint Discrimination Unit (JDU) and the civilian Examination Unit, which had been combined into the new civilian CBNRC.

The new home, which had previously housed the JDU, was the La Salle Academy on historic Sussex Avenue in downtown Ottawa. The first building at the site was built in 1847 as the College of Bytown. The light grey stone Georgian building with gabled roof was later augmented with additional structures over the years, culminating in 1934 with a classroom wing on the adjoining Guigues Street that became the CBNRC’s home. The main tenant of the property remained a Catholic school for boys throughout the CBNRC tenancy. The school auditorium below was used by a local theatre company, and Branch staff would watch rehearsals that featured later luminaries such as Christopher Plummer and William Shatner.

Canada in the immediate post-war years was flourishing but heavily indebted, and austerity was the order of the day. Space was tight from the beginning; staff could requisition a new pencil only when the nub of the previous one was surrendered. Despite this, a spirit of collegiality was immediately evident. The military veteran and civilian personnel mixed easily. Drake encouraged a variety of sports clubs and activities, including hockey, softball, and dances. This was also when the CBNRC bowling league was born; it would continue for decades as the activity around which the Branch’s social calendar was built.

Staff may have enjoyed their time at the Academy, but it was not a long-term option. Sharing a building with a school and theatre was obviously an imperfect arrangement. There was little space for growth or large machinery, and classified waste had to be shipped to industrial incinerators elsewhere in Ottawa. CBNRC had only the third floor to itself, and when it managed to secure two rooms on the second, they were shortly thereafter claimed back by the school. As a result, work soon began on a replacement building, the first the Branch would have all to itself.

LaSalle Academy still exists today, in almost the same exterior form as during the war. It became a Federal Heritage Building in 1988.

CSE’s Many Homes, Part 2 – 345 Laurier

This is the second part in a multi-part series of historical articles about CSE’s many homes. The buildings that have housed CSE reflected the organization itself: ever bigger, more complex, more effective, and strangely unique. If you missed Part 1, you can find it below.

The Examination Unit (XU), CSE’s predecessor organization, occupied its second home in March 1942. The building at 345 Laurier Avenue East was an oversized Edwardian mansion originally built for a prominent Ottawa lumber baron. The surrounding neighbourhood, known as Sandy Hill, had peaceful, tree-lined streets that belied its proximity to the city’s bustling core. The building’s neighbour was the residence of the Prime Minister.

The XU originally occupied the second floor, with the Army’s communications intercept group, the Discrimination Unit (DU), occupying the first. The entrance was guarded night and day by members of the Veterans Home Guard. Employees had to show identity cards to enter, and all scrap paper was shredded and burned each evening. Employees were discouraged from joining outside organizations, even the public library. The real name of the XU was known only internally; to the public, 345 Laurier was the National Research Council Annex. Employees even had job titles like “lab technician”, or “researcher”, to disguise what they were really doing.

As the war progressed, the size of XU increased, eventually forcing the Discrimination Unit out and into their own quarters in 1943. The DU, and its dynamic head Edward Drake, would reunite with the XU to form CSE’s first true predecessor organization two years later.

Ottawa today is very different than the city in which the Examination Unit began. The mansions of Sandy Hill were repurposed as embassies, diplomatic residences and student accommodation in the decades following the war. The house at 345 Laurier was itself subdivided into apartments in 1948 and then replaced with an apartment complex in the late ‘60s. It remains there today.

CSE’s Many Homes, Part 1 – Building M2

In 1941, CSE’s wartime predecessor began with just a handful of people, working mostly with pencil and paper. But from the very start its successes and the importance of its mission drove growth, and that growth demanded more and different accommodation. The buildings that have housed CSE reflected the organization itself: ever bigger, more complex, more effective, and strangely unique.

The beginning could hardly have been more modest: Nine people, in two borrowed rooms, armed with little more than their intellect. But as is often the case, the necessities of war led to invention and innovation.

Canada had run a few fragmented radio-intercept programs since the 1920s, but it was far from certain that these would coalesce into something more with the advent of the Second World War. On the contrary, when the Department of National Defence considered the issue in December 1940, it concluded that “the cost of such an organization in Canada could not possibly be justified at the present time.”

It was instead the Department of External Affairs (DEA) that became the driving force for a more ambitious approach. Led by the renowned Undersecretary of State, Norman Robertson, the department approved the creation of a small bureau to be opened in June 1941. It would sit administratively within the National Research Council (NRC) but report operationally to the DEA.

The Examination Unit (XU), its name purposely obscure, was assigned rooms 203 and 204 on the second floor of Building M2, which otherwise housed the NRC’s aerodynamics section. Building M2 was part of a new NRC complex on Montreal Road, east of the city. Surrounded by bush and farmland, the location offered both space and security. The structure, newly built in the modernist European style, was steel and concrete covered in white stucco, in contrast to the traditional neo-Gothic style of prominent buildings downtown.

Building M2 still exists today as part of the much-expanded NRC campus on Montreal Road, although now it is used mostly for administrative purposes. The region is now considered the inner suburbs. One of its neighbours, almost visible just 1500 metres to the north, is the Edward Drake Building, CSE’s current headquarters.

SAPPHIRE and NOREEN

In 1948, British intelligence confirmed that acoustic and electro‑magnetic emissions from cipher machines could be intercepted during decryption and read as plaintext. This meant that key intelligence among western nations could potentially be intercepted and read by adversaries.

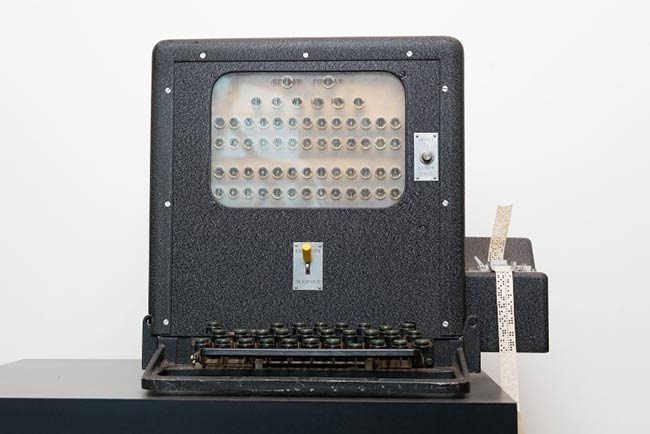

Canadians working for the CBNRC, CSE’s predecessor organization, took up the challenge of tackling this problem. Using standard, off‑the‑shelf parts, and for a cost of less than $200, our crypto engineers built the SAPPHIRE – a miniature version of the encryption workhorse at the time, the ROCKEX. The SAPPHIRE had a keyboard input, read key tape, and had an illuminated display output.

It was powered by a hand‑crank and processed about 10‑12 characters per minute.

Canada shared this new machine with its partners in the UK and the Brits gave the Canadian SAPPHIRE their seal of approval. No emissions. No compromising acoustics. No worrying about our adversaries listening in, and a machine that outperformed many of its contemporaries. The SAPPHIRE was perfect for deployment behind the Iron Curtain.

Shortly after the British Government Security Headquarters approved the Canadian machine, they improved the design of the mechanical SAPPHIRE with their own battery‑powered, motor‑driven machine – the NOREEN.

Before long, the British‑built NOREEN replaced the SAPPHIRE (still in prototype) and was widely distributed and used by Canada, the UK and her allies.

Decades later, the Canadian‑designed SAPPHIRE prototype was discovered in a storage closet at CSE headquarters in Ottawa, packed alongside unused office equipment. We recovered and restored it, and we are proud to have it here in our collection alongside its cousin, the NOREEN.

WW Murray

At exactly 5:30am on April 9, 1917, The Canadian Expeditionary Force attacked Vimy Ridge, a heavily fortified strategic location that had been held by the Germans since 1914. The Canadian offensive succeed where others had not, in part because intelligence was used inform military planning.

One of the soldiers involved in the Vimy Ridge offensive was Lieutenant William Waldie “Jock” Murray, in charge of the Scout Section of the 2nd Battalion. Murray used information from cables to help track the movement of enemy troops. Through his experiences in some of the deadliest battles of WWI, Murray became convinced that intelligence was a vitally important tool.

With the outbreak of the Second World War, Murray was recalled to service and in 1940 he was put in charge of the Canadian Army’s wireless intelligence program. In June 1941, he joined other senior officials to extoll the virtues of signals intelligence (SIGINT) as a Canadian advantage. This meeting would serve as the catalyst for the creation of the Examination Unit (XU), Canada's first civilian SIGINT office, which was established on June 9, 1941.

In 1942, Murray, by now a full Colonel, became Canada’s first Director of Military Intelligence and spent much of the remainder of his service lobbying for the creation of an independent Canadian signals intelligence organization. He had two notable partners, Colonel Edward Drake and Lieutenant Charles H. Little.

As the war came to an end in 1945, these three argued for a Canadian peacetime SIGINT organization. Murray believed that Canada had demonstrated its competence and value in signals intelligence and cryptanalysis to its allies and argued that Canada should be able set its own intelligence priorities.

On September 1, 1946, thanks in part to the advocacy of William Murray, whose appreciation for intelligence was forged almost 40 years earlier, the Communications Branch of the National Research Council (CBNRC) – later to become CSE – began operations.

Col. Murray, who had been a writer for the Canadian Press after the First World War, continued as a freelance writer in the wake of the Second World War. He wrote a weekly column in the Legion magazine under the pen name “The Orderly Sergeant,” and authored books and poems relating to his war experiences.

When he died in 1956 at only 65 years old, he left behind a very public legacy of war time stories and bold accomplishments. However, what people did not know was the extent of his classified work and how it contributed to the creation of the CBNRC.

M-209: The First FVEY Cipher Machine

In 1940, as the Second World War raged across Europe, mechanical engineer and inventor Boris Hagelin from neutral Sweden travelled to the United States to try and find buyers interested in his latest invention, the C-38 tactical ciphering device.

The device featured six key wheels used to set the initial state of the machine. The six wheels each had a small movable pin aligned with each letter on the wheel. These pins could each be positioned to the left or right, with the left position ineffective and the right position effective. Further, each key wheel contained a different number of letters, and a correspondingly different number of pins. As a result, the C-38 provided a possible 101,405,850 combinations.

To encipher a message, the key wheels would be set according to a daily key provided by the operator. Text was then entered one letter at a time by setting an alphabetic ring to the desired character, then turning a hand crank to advance the key wheels and print the cipher-text letter on paper tape. The entire process was mechanical, requiring no electricity to operate.

About the size of a lunchbox, and weighing a mere six pounds, The C-38 was easily portable and ideal for use by soldiers in the field. The United States military was impressed with Hagelin’s machine and signed an agreement to put it into wide use by its forces, re-designating it the M-209. By the end of WWII more than 140,000 M-209s were produced in the U.S., and Hagelin became the first cryptographic inventor to become a millionaire.

The M-209 was still in service in 1950 when the United States, as part of a United Nations Resolution 83, entered the Korean War. While the M-209 was not secure enough for high-value communications – it was estimated that DPRK and Chinese codebreakers could decipher M-209 messages in under 10 hours – it was still ideal for short-term, tactical messages to and from deployed units.

The Americans made the M-209 available to all 16 countries in the United Nations Command (UNC), including Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand, making it the first cipher machine to be used in theatre for secure communications among all 5-Eyes partners.

A pair of M-209 cipher machines are currently on display in the Edward Drake Building as part of CSE’s collection of historical artifacts.

Evelyn Davis

November 11, 2007, was a particularly cold Remembrance Day at Intrepid Park in Oshawa, Ontario. The wind that rolled off the great lake went right through the small group of locals and visitors, including representatives from military and civilian intelligence services across Canada, who had come to lay their wreathes at the cenotaph where Camp X once stood.

After the ceremony people started filing into the Whitby Centennial Building, to warm up with some coffee and pie. The Camp X Historical Society was holding a reception, attended by around 250 people.

A small exhibit of artefacts was set up for the occasion. Hanging on a coat rack next to a table with letters, photographs, and declassified documents, was a neatly pressed, very small Canadian Women’s Army Corps (CWAC) uniform. It belonged to the 84-year-old woman who was standing behind the table, talking to visitors. Evelyn Davis, also known as “Jimmy,” from her Camp X days (for the way she pronounced her maiden name Jamieson—Jem-i-sen), where she had worked as teletype operator during the Second World War.

“It doesn’t fit me anymore,” she said about the uniform.

Then somebody responded, “But you will always fit the uniform, Evelyn”.

A 20-year-old Evelyn Jamieson had joined the CWACs, in March 1943, in response to recruitment posters calling for women to relieve soldiers for active duty. Evelyn had learned about wireless radio and already knew Morse Code before joining. So, on enlistment, she put down wireless radio training as a preference for specialization. One year later, in March 1944, her request was granted.

After completing her specialization training in Kingston she was supposed to return to Orillia, but her orders were changed unexpectedly. On June 1st 1944, along with two other CWACs, she was transferred to the Communications Center (HYDRA) at Camp X, which up until just a month prior to their arrival had been a Top Secret spy training school. Although there were a number of CWACs who had been at the Camp long before their arrival, the three of them would be among the first to work on the super secret HYDRA communications, a job for which knowledge of Morse Code was imperative.

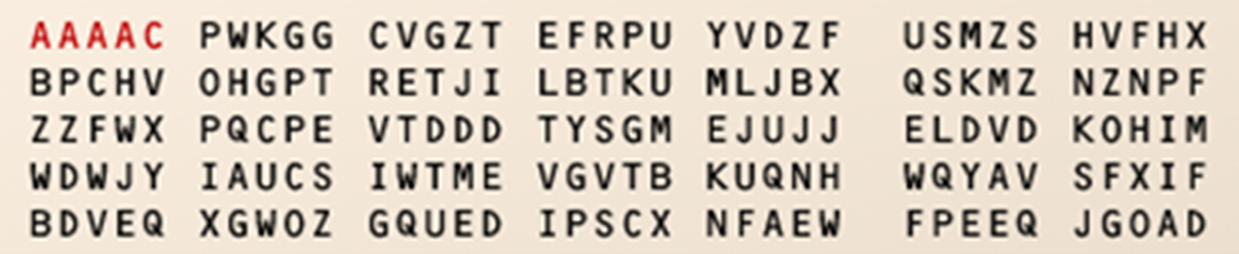

Evelyn worked, along side many others, men and women, military and civilian, relaying encrypted raw traffic in 5-letter-group code between Washington, New York, England and Ottawa. Her family didn’t know where she was, or what she was doing, nor did they ask. Everyone was aware that in wartime, secrecy was paramount. It wasn’t until years later, when she learned that she had actually been sending raw intercepts to Bletchley Park in the UK, that Evelyn understood the true weight of her work at HYDRA and the responsibility she bore in keeping it secret.

When Evelyn was discharged from the military, at the end of October 1945, as a Sergeant with ‘B’ trades in ‘Keyboard’, nobody knew what a keyboard specialist was. After her military service she continued to work in total secrecy as a civilian communications officer at the Top Secret communications hub, until her marriage in July 1946 to Lee Davis, whom she had met at Camp X.

Evelyn continued serving as a war historian, giving presentations from first hand knowledge, to generations, even occasionally spelling out their names in “dit-dit-dit dash-dash-dash” Morse Code, until she was too frail to continue at age 89. But at the end of that very cold Remembrance day in 2007, she was still going strong. As guests were preparing to leave, somebody handed Mrs. Davis a small roll of teletype ribbon and asked if she knew which way it fed into the cipher machine. She turned it around in her hand and said “It’s just common sense…” indicating three holes up and four holes down. And then “Jimmy” started reading aloud the letters designated by the punch holes that were made 63 years ago.

Evelyn died in 2016. Shortly before her death, she requested the uniform in which she processed thousands of encrypted messages be kept with the rest of the Camp X Historical Society artefacts donated to CSE in 2013.

It now hangs in CSE’s Museum, as part of the Camp X Communications display.

A part of our history.

Mrs. Oliver

Mary Oliver moved to Ottawa in 1940. Thirty-four years old, a mother of two young boys, and recently divorced, Oliver had left her home in Vancouver to start a new life and career on the other side of the country. Over the next two decades she would cultivate a significant legacy in the nation’s capital, building on her keen mind, quick wit, and compassionate nature to become one of the founders of the Communications Security Establishment.

By September 1946, Canada’s wartime cryptologic agencies – the civilian Examination Unit (XU) and the military Joint Discrimination Unit (JDU) – had evolved into the newly established Communications Branch of the National Research Council (CBNRC – renamed CSE in 1975). Oliver, who had started with the XU in 1941, stayed on throughout the war and the merger with JDU, where she worked alongside Edward Drake, who later became CBNRC’s first Director.

Her title of Administrative Assistant did not do justice to the scope of her responsibilities. She spent years maturing as a professional amid the growth and complex evolution of Canada’s cryptologic and SIGINT organizations. She was a member of the Canadian delegation to the 1946 Commonwealth SIGINT Conference in London, at which Canada negotiated an equal and independent post-war intelligence partnership with the United Kingdom.

Oliver’s wealth of experience proved invaluable in managing the logistics, recruitment needs, and business requirements involved in standing up a cryptologic intelligence agency. Her many duties also included overseeing personnel management and recruitment, a responsibility she took to heart.

The XU and the CBNRC in its formative years had a more familial atmosphere than a corporate one. In her role as the personnel and recruitment officer, Oliver’s maternal approach to the staff played a significant part in maintaining that homey environment. This was especially true for the young women who had signed up to do important work for the Canadian SIGINT effort during and after the War.

Describing her work at CBNRC and her relationship with her fellow employees, Oliver wrote:

A good deal of personal counselling has been done in [my] office; much hair has been let down and many minor sources of friction removed by this informal method. It would be only too pleasant to brighten this document with a few of the tales that have been told in my particular niche. Everything had been discussed from questions of high policy to babies’ teeth.

And, in reflecting on her time at the XU, Oliver wrote:

The period spent at 345 Laurier will be an unforgettable interlude, I think, in the lives of all who worked there. Discipline was not very rigid and working conditions were ideal. We had all the conveniences of home, a kitchen with grill and icebox, three tiled bathrooms, bright airy rooms to work in, a lovely enclosed garden where we could enjoy sun baths at noon or a game of ball at the tea break. Tea in the kitchen was a wonderful institution. Then we were advised that the working day was to be shortened and that, if we wished, we could shorten it ourselves still further, we almost thought of giving up ‘tea’ but decided it would be a mistake. It had become such an institution that we considered it unwise to discontinue the habit until the entire staff had been disbanded.

This atmosphere, established and nurtured by Oliver, stayed with the organization over the decades, through growth and transformation, and remains part of what defines the culture of CSE today.

By 1949, Oliver’s extensive experience in the administration of Canadian SIGINT and Communications Security (COMSEC), and her growing reputation as a respected member of the Five Eyes community made her an ideal candidate to, once again, establish a new office: Canadian intelligence Liaison Officer to London. In February of that year, she was appointed Liaison to GCHQ in London, becoming CBNRC/CSE’s very first Foreign Liaison Officer.

When she returned to Ottawa a year later, Oliver resumed her considerable responsibilities as Administrative Section Head, which covered personnel, recruitment, drafting and implementing security procedures, and organizational administration. She laid the groundwork for CBNRC’s administrative framework, which she continued to develop for another decade.

By 1963, CBNRC had nearly doubled in size. Later that year, Mary Oliver retired and the job she had been doing singlehandedly for 17 years was taken over by three separate specialists.

Upon her retirement, the following was published in an employee newsletter:

Since coming to CBNRC seventeen years ago, Mrs. Oliver has, through her ability to understand human nature and her competent evaluation of aspiring applicants, shaped and molded the staff of CBNRC so that today the national and international distinction enjoyed by this organization is a direct result of her successful recruitment and a tribute to it.

A manifestation of gratitude and appreciation was displayed recently at her retirement party, when the largest crowd ever to attend such a function gathered to compliment her popularity and express her prominence within the hearts of the members of CBNRC […] Mrs. Oliver will be missed by her many friends and colleagues, who have come to love her for her kindness and understanding, as well as her ability in administrative and personnel services. Although she will no longer be at the Branch, her contribution will be felt for many years through the efforts and successes of those she selected.

As recognized by her colleagues and contemporaries, the contributions of Mrs. Oliver were far-reaching and significant, and touched almost every part of the establishments for which she worked. Oliver's legacy is not only one of dedication to Canada's early SIGINT organizations, but more importantly, to their people.

A Brief History of Hockey at CSE

Sports and physical activity have been an important part of CSE from the very beginning. From the popular bowling leagues of the early years – Edward Drake, CSE’s first Chief, was an avid bowler – to the soccer, volleyball and other games our employees play today it’s hard to imagine CSE without team sports.

Of course, being Canada’s national cryptologic agency, we have a special place in our hearts for hockey.

Pick-up hockey and recreational leagues have come and gone at CSE since its founding in the 1940s, but the teams our organization fields today date back to 1995 when the first “official” CSE Hockey Team was formed to take part in a charity tournament organized by the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF).

CSE was given the opportunity to play when another team dropped out at the last minute. With only a week before the first puck drop at the tournament, a CSE team of nine players was quickly pulled together.

Despite the short notice, the ’95 CSE team must have handled themselves well enough on the ice to make a positive impression, as they were invited to a larger tournament the following year featuring teams from across the S&I community. Wanting to look a little more like a real hockey team, as they would be going up against established squads from partner organizations like CSIS, CAF, and the RCMP, the CSE team invested in proper hockey sweaters, the letters CSE proudly emblazoned across the front, and grew its roster to 17 players.

Participation in this annual S&I tournament, as well as several other charity hockey events over the course of the next few years, inevitably led to CSE employees seeking more regular games. And so, in 2002 the first ongoing recreational league, the Everyman’s Hockey League (or EHL), was formed.

The EHL was, from the beginning, created to be a fun league where sportsmanship and camaraderie were more important than winning and losing. And, despite the name, the EHL has been co-ed since its founding. At the start most EHL players did not own proper hockey equipment, and it was not uncommon to see bicycle helmets, gardening gloves, and even styrofoam “goalie pads” held in place with hockey tape. One of the EHL goalies was also a member of the CSE Choir and would sing the national anthem before some of the games.

On more than one occasion the EHL was even able to play at the Corel Centre (now Canadian Tire Centre), home ice of the NHL’s Ottawa Senators.

The EHL proved popular not only among CSE employees, but also among our Five Eyes partners. Colleagues visiting CSE from Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States would often ask to play hockey with a CSE team because they wanted a chance to “do something Canadian” while visiting Ottawa.

Since the founding of the EHL recreational hockey has only continued to grow at CSE. As of 2021 there are not one but three CSE hockey leagues, each with weekly games. CSE also continues to participate in the annual tournament with our S&I partners, often entering with two or even three teams.

We’ve even taken home the trophy from time to time.

A Canadian flag for CBNRC

Until 1965, the flag flown to represent Canada was known as the “Red Ensign.” It consisted of the Union Jack in the upper left corner on a red background, and the Canadian coat of arms in the lower right corner.

After years of unofficial debate around the idea for a Canadian flag, Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson formally introduced the idea to Parliament in 1964. While some argued for the Union Jack to remain in a place of honour on any new design, others advocated for a unique, completely Canadian flag.

To help resolve the flag debate, Prime Minister Pearson created an all-party Parliamentary committee. He gave them six weeks to decide on a final design from around 5,000 submissions that were collected from across Canada.

On October 22, 1964, the committee voted unanimously in favour of a design that was known as the “Stanley Flag”, nicknamed after its designer, George Stanley. The idea then went to Parliament where it was approved and then given Royal Assent by the Queen in January 1965.

On February 15, 1965, the Canadian flag flew over Parliament Hill for the very first time.

That same day, CBNRC (as CSE was called at the time) followed suit with their own flag-raising ceremony.

Everyone gathered outside to witness this historic event as Edward Drake, CBNRC’s first director, lowered the Red Ensign for the last time. The old flag held a special place in the hearts of many CBNRC employees, some of whom, like Drake himself, had served under it during the Second World War. And yet, it was a celebratory occasion as the brand-new Canadian flag was raised and unfurled for the first time in front of Canada’s national cryptologic agency.

The creation of a Canadian flag, much like the creation of the CBRNC as an independent intelligence organization only twenty years prior, represented another major turning point towards Canada emerging as a mature nation on the world stage.

In an internal publication at the time, a CBNRC employee wrote:

“The birth of our flag at least represents the initial phase of a solution which is designed to see Canada emerge as a mature nation. Aside from Canada’s contribution to World Wars I & II, the flag alone is of our making, the manifestation of which represents the birth of a new era – for this we should be proud and strive with vigour towards a complete independence and a unified nation.”

Today, the Canada Flag continues to fly proudly in front of the Edward Drake Building in Ottawa.

Drake’s family kept the Red Ensign that he lowered in 1965 and donated it to CSE. It remains today at CSE headquarters as part of our historical artifact collection.

Building on a History of Innovation: The Host-Based Sensor (HBS) Program

The year 2010 was marked by an increasingly hostile cyber environment, and unprecedented cyber threat activity directed at Government of Canada networks. It was clear that a new capability was needed to protect against sophisticated cyber threats. As a result, CSE took the lead in helping improve the cyber security of over 110 federal departments and agencies.

A new and effective defence was needed not only at the perimeter, but also within government networks. A cyber defence system with an ability to respond quickly and automatically to malicious activity, neutralizing it as it occurred. And, as if that were not enough already, this new defence also needed to effectively protect up to a million desktops, laptops, and servers without slowing down the network.

This was a big challenge, but from the start it was clear that this was also an opportunity not just to help defend government networks, but to contribute to the broader cyber security of all Canadians.

Since no commercial product existed that met these requirements, CSE decided to do what it has always done throughout its history – innovate and develop something new to meet the challenge. CSE’s IT Services division, now the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security (Cyber Centre) had the expertise and the drive to get the job done. Development began in November 2010 on what would soon become CSE’s Host-Based Sensor (HBS) Program.

The HBS Program began with a team of six CSE employees, working on computers they had built themselves in a space that had been, up until that moment, a storage room. But from humble beginnings often come great things. Now, eleven years later, the HBS Program has been deployed throughout Government of Canada network where it plays a significant role in protecting against cyber threats.

In 2017, with the participation of the UK National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC), the HBS Program went international. The NCSC ran a trial on a UK government IT network using a version of CSE’s HBS. They reported great success from this trial and are currently growing their program under the brand name Host Based Capability (HBC). Sharing HBS means Canada and its partners can warn each other of their own observations of early malicious activity, and do not have to fall victim to the same malware as may affect other parts of the world.

And recently CSE has even started using the knowledge derived from this data to inform the Canadian Internet Registry Authority (CIRA)’s Canadian Shield, which means that all Canadians can also benefit from the Cyber Centre’s experience.

Over the past 75 years, through shifts in technology and tradecraft that have taken us from the very beginnings of the Cold War to the challenges of cyberspace today, CSE has maintained a tradition of innovation to meet whatever challenges it needs to overcome. The HBS Program is just one of the latest results of this proud tradition that has helped CSE fulfill its mission.

CSE’s First Green Initiative

From 1941-45, the Examination Unit (XU) was Canada’s first civilian SIGINT organization. It’s focus was on wartime decryption of traffic from the Vichy Government in occupied France, as well as other military and diplomatic communications.

Mary Oliver was known as the XU’s “Unit Secretary”, but in her role as Executive Assistant to the Director she was in many ways responsible for administration of the entire organization. Taking care of every aspect of the running of the place, including recruitment, training, and operations, the resourceful Mrs. Oliver was often called upon to find solutions to unusual problems.

One such problem came about in 1943, when XU Director F.A. Kendrick (a codebreaker on loan from Bletchley Park) inquired with Washington about the possibility of acquiring material that might be of use to the XU’s Japanese military decryption section. While it was typical at the time for such requests to take months to see results, Mrs. Oliver recalls being surprised when, within a few days, a notice came to XU headquarters on Laurier Avenue in Ottawa that there was a special delivery from the U.S. Signal Security Agency waiting under armed guard at the train station: five tons of IBM punch cards.

“I was given the horrible task of finding space for it at once,” Mrs. Oliver recalls. “The Public Works Department could give me no assistance, and the Director of Military Intelligence was not really interested […] I went about the building, measuring struts and cross-struts to see if they could support the boxes of cards. Owing to the fact that IBM cards will warp if not kept in a dry place, it was necessary to find a location where they would not deteriorate. Finally, after taking a great many measurements, a Public Works Department engineer agreed that the material could be stored on the third floor and in the attic on the fourth floor.”

One night, when the entire staff had gone home, Mr. Kendrick went to the Union Station and accepted the delivery. It took three hours to stow it all away, with the local Veterans' Guard having been elected on fatigue duty to do the job.

Despite the massive effort involved in delivering and storing the IBM punch cards, they ended up being of very little use. According to Mrs. Oliver:

“The cards remained above us for two solid years and I don't think more than half a dozen of them were ever used.”

At the end of the war, as Mr. Kendrick prepared to return to the UK he felt the “white elephant” in the attic of the XU ought to be dealt with. And so the first ever green initiative by a Canadian SIGINT organization was undertaken when Mary Oliver decided that, rather than have the cards destroyed, they would be sent to be pulped by Booth's Paper Company.

“Thus five tons of IBM cards came to a useful end in the form of cake boxes, ice cream cartons etc.”

Edward Drake

Considered by many to be Canada’s cryptologic pioneer, from 1940 to 1971 Edward Michael Drake was the architect of both the Canadian Army’s SIGINT service during the Second World War, and the establishment of Canada’s civilian Signals Intelligence (SIGINT) service in the post-War era. He was the Director of the first integrated, national SIGINT organization in Canada, the wartime Joint Discrimination Unit (JDU), which combined wireless intelligence and code breaking in one facility and was the driving force behind the creation of Canada’s wartime codebreaking body, the Examination Unit (XU).

While Drake’s SIGINT service reported extensively on German Army operations during the first half of the war, from 1942 onwards it focused on assisting the United States and Britain in providing SIGINT support to Allied operations against the Japanese Empire. Ed Travis, the Head of the UK’s Bletchley Park, described Drake’s SIGINT unit’s work on Japanese military traffic as achieving “an extremely high standard by comparison with that available from other sources.”

In recognition of his invaluable contribution to Allied SIGINT and cryptography during the Second World War, Edward Drake received the U.S. Legion of Merit (Officer) on 18 July, 1946; The award was accompanied by a citation letter from President Truman, which reads:

“Lieutenant Colonel Edward M. Drake, General Staff, Canadian Army, rendered exceptionally meritorious service for his country and the United States from January 1943 to August 1945. Colonel Drake’s exemplary spirit of international cooperation in an extremely technical and specialized field was an exceptionally meritorious contribution to the successful prosecution of the war.”

Colonel Drake was given special dispensation by HRM King George VI to wear the U.S. Medal as part of his Canadian uniform.

Allied SIGINT leaders often referred to Canada’s significant contributions throughout the Second World War, citing the work of LCol Drake and the Discrimination Unit he commanded. This in turn led to strong support for continued development of Canadian SIGINT in peacetime.

Based on these extraordinary achievements, and to no lesser degree the personal calibre of his character, Edward Drake garnered support for the creation of an independent Canadian cryptologic agency. At the end of the War, Edward Drake was tasked by Prime Minister Mackenzie King’s government with building and directing Canada's first permanent cryptologic agency, the Communications Branch of the National Research Council (CBNRC), which would later be renamed the Communications Security Establishment (CSE).

What made Edward Drake unique in the field of signals intelligence and communications security was his vision, a worldview that saw beyond the immediate crisis and even his own lifetime. Even in the earliest days of the Allied signals intelligence and cryptology cooperation during the Second World War, Drake had the foresight to recognize the remarkable international partnership the Five-Eyes would become. He dedicated his life to this important international partnership, and to securing Canada’s place in it as an equal and independent member. In 2019, Edward Drake became the first Canadian to be inducted into the U.S. National Security Agency’s Hall of Honor.

Edward Drake was an exceptional leader. Driven by an analytical mind and an unwavering determination to do the right thing, he earned the trust of his superiors, the respect of his peers, and the loyalty and affection of those who worked under his leadership.

When Edward Drake died on February 8, 1971, he left an enduring legacy in the intelligence community in Canada and among Canada’s allies. It is on this foundation that the present-day Communications Security Establishment (CSE) was established and continues to operate to this day.

Robert S. McLaren, CSE’s first liaison officer

At the beginning of the Second World War, Canadian armed forces were already collecting raw ciphered signals from enemy military and foreign mission communications traffic. Canadian Military intercepts of enemy SIGINT were used mostly to locate enemy positions and movements, based on metadata, and sent to Britain and the USA.

With the Nazi occupation of France, Canada was encouraged by the Allies to put together a civilian office that would decrypt signals traffic content, such as messages from the Vichy Government and other military and diplomatic communications. On occasion, depending on the type of communications, some content could be analyzed by the Military Discrimination Units, but it was the civilian Examination Unit (XU) that would regularly decipher content and disseminate intelligence to Canadian Foreign Affairs as well as to the Allies.

Robert S. McLaren, known affectionately as “Mac” to his colleagues, rose to prominence in Canadian cryptography as a member of the XU. His work would typically involve deciphering communications intercepted at places like Canadian Forces Station Leitrim, which would then be provided to both Canadian and American authorities.

As a cipher analyst, he frequently worked with American counterparts throughout the war, and it was in this capacity that he met and became friends with William Friedman, one of the founding fathers of the NSA.

In February 1950, following the establishment of the CANUSA agreement for post-war signals intelligence sharing between Canada and the United States, McLaren became the very first Communications Branch Senior Liaison Officer in Washington, or CBSLO, a position he held until August 1951.

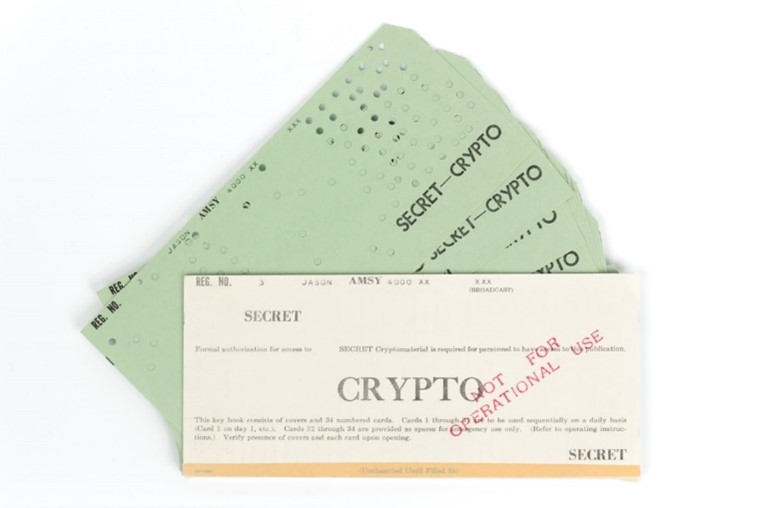

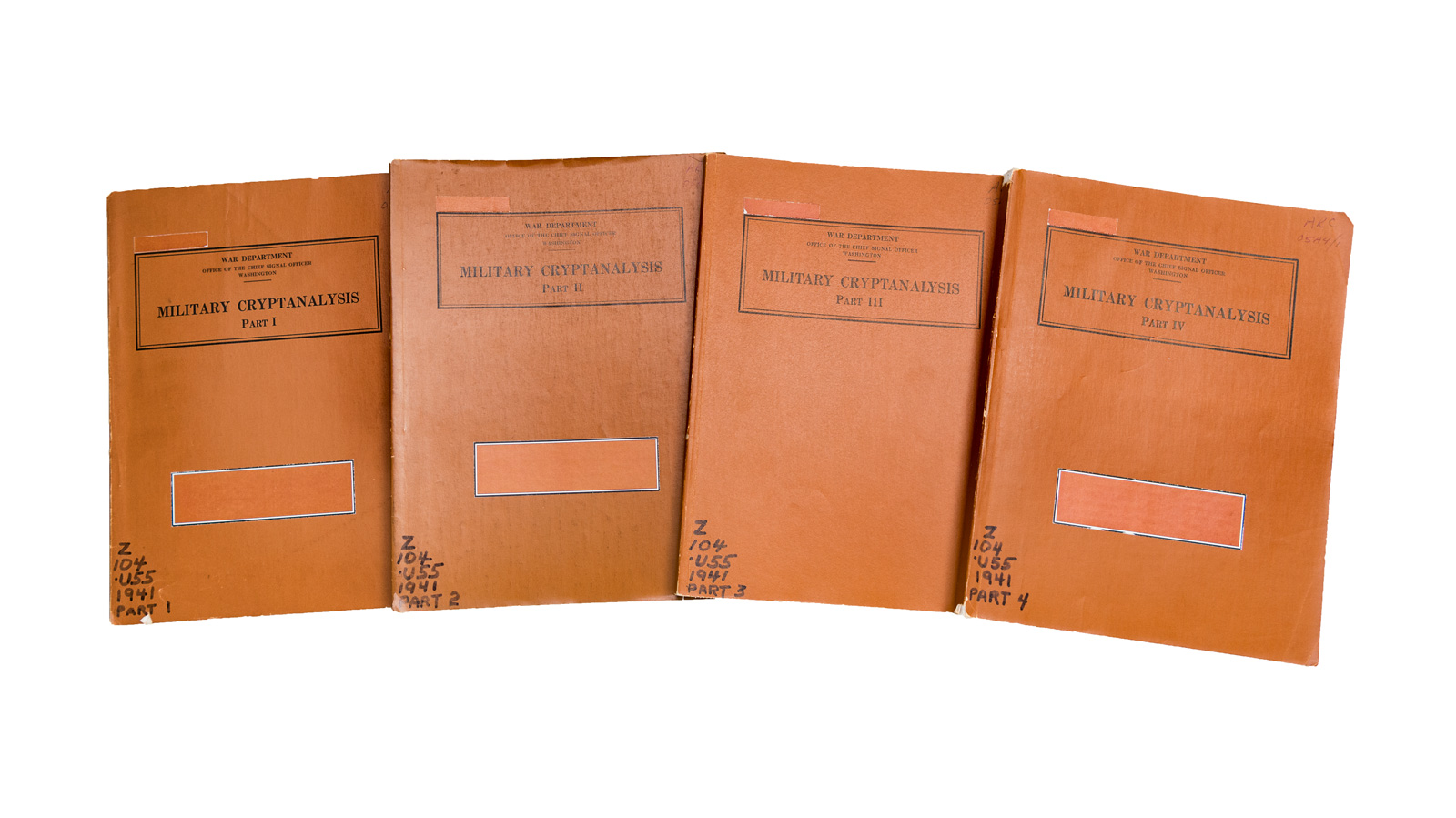

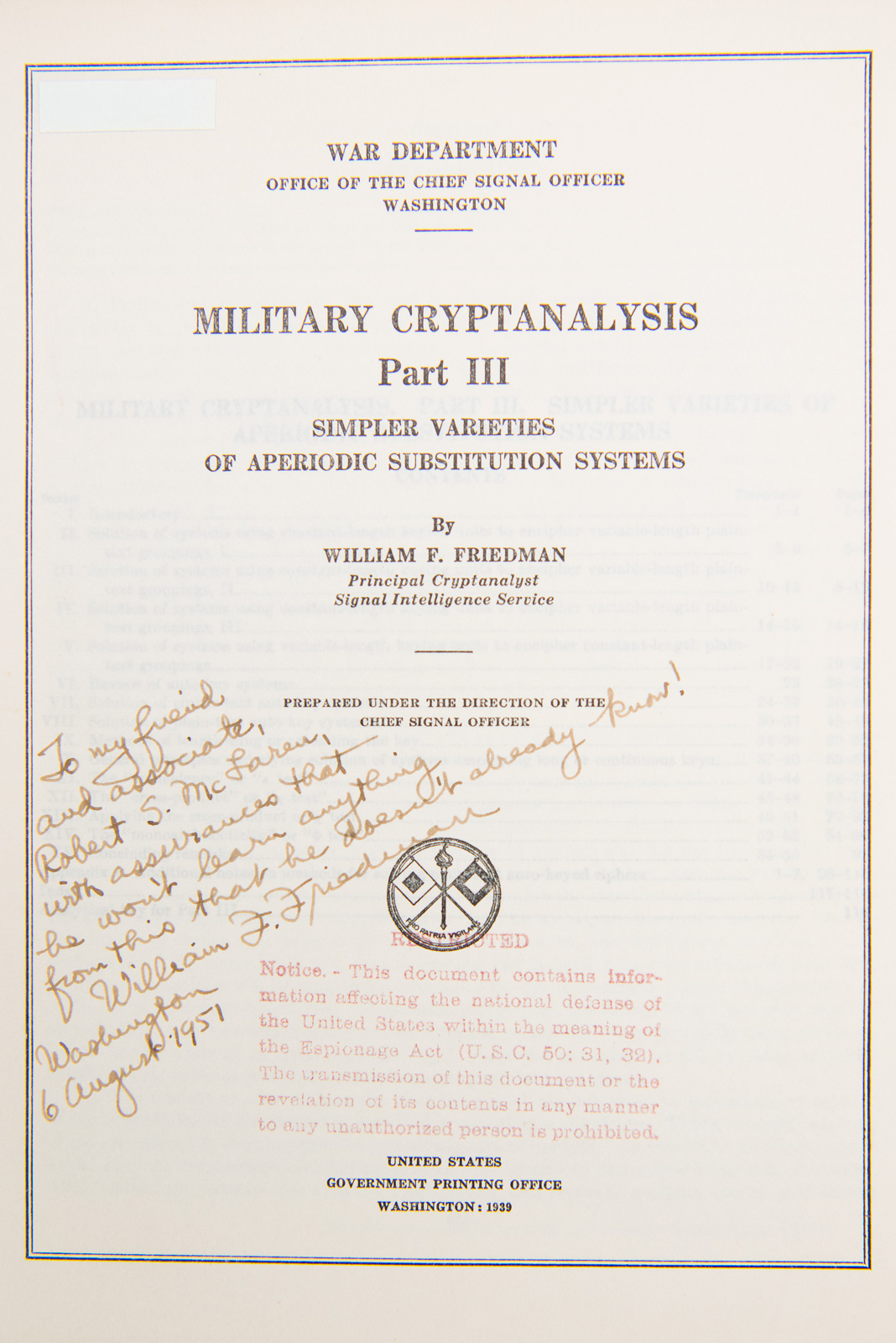

During his tenure as CBSLO, McLaren so impressed his American colleagues that William Friedman, considered by many the founder of American cryptography, gifted him with a four-volume set of the US War Department’s Military Cryptanalysis manuals, which Friedman himself had written in 1938. Friedman wrote a personal inscription in each of the volumes, including:

“To my friend and associate Robert S. McLaren, with assurances that he won’t learn anything from this that he doesn’t already know!”

ROCKEX – The Keeper of Secrets

It was 1946. The Second World War had ended but the Cold War was only just beginning. And, the task of maintaining a secure system for transmission of highly classified information was as important as ever, if not more so.

The answer to this challenge was HYDRA, a top-of-the-line, Canadian designed telecommunications relay station that was built and deployed to great effect during the war. While HYDRA was developed in Canada, operational control of the system remained in British hands.

Cooperation was the key to Canadian signals intelligence success. As outlined in a memo to Norman Robertson, then Under-Secretary of State for External Affairs, a Canadian takeover of HYDRA would "contribut[e] substantially to the post-war signal intelligence effort of the Commonwealth and the U.S.A.”

The beating heart of HYDRA was the Rockex cipher machine, developed by Benjamin de Forest Bayly, an electrical engineer from Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan.

The Rockex was a landmark development in the evolution of cryptography. Previous generations of cipher machines, such as the famous German ENIGMA, used mechanical rotors to scramble messages. These rotors devices could generate complex codes, but highly specialized cryptographers had already proven – again with the German ENIGMA – that such codes could be cracked.

Instead, the Rockex used teleprinter technology to shuffle two streams of data together. Based on the Vernam Cipher (a one-time tape encoding technique), it used a pair of cipher keys – one for the sender to encrypt the message, and another for the receiver to decrypt it. As the name suggests, keys were used only once. Without the key tapes, it would be impossible to read Rockex messages. What it produced was an unbreakable off-line cipher machine that could encrypt and decrypt in real time, as fast as the operator could type.

When Bayly designed and built his cipher machine he built it to last, and it lived on to safeguard the security of communications well into the post-war period. The UK and Canada selected the Rockex as their system of choice for Top Secret diplomatic traffic. From the mid-1950s onwards, NATO members also used it for their most sensitive communications.

“Such was the success of [Bayly’s] efforts,” writes University of Calgary Historian John Ferris, “that variants of the Rockex family were still being utilised in British embassies until the 1970s.”

The last Rockex was officially decommissioned in 1983, capping off 40 years during which these incredible Canadian machines were in service at home and around the world.

How CSE got its badge (Part 2)

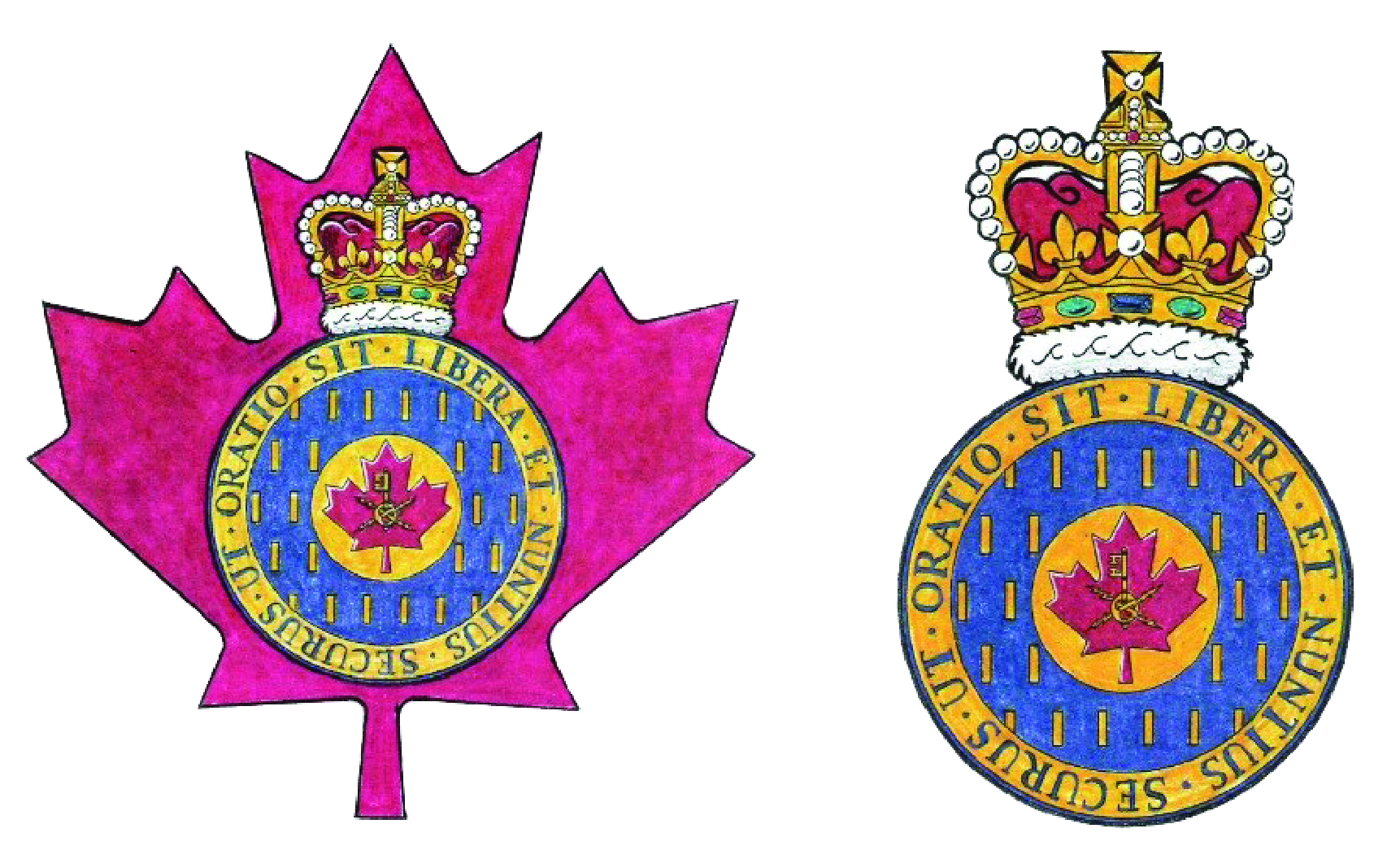

On 1 May 1991, CSE Chief Stewart Woolner announced in a memorandum to all employees that CSE would begin development of “a unique CSE crest or logo to appear on such items as envelopes, pins, documents and publications that will be internal to CSE, and public notices, including recruiting advertisements and conference material.” All staff were invited to submit suggestions for the design of a badge “reflecting CSE’s unique mission,” and T Group Graphics and Photography Unit (now known as Creative Services) would be asked to prepare “a professional representation of the most promising entries.”

Several employees took up the challenge and submitted ideas for badge designs. One submission was a drawing that included a maple leaf, a lightning bolt, and a skeleton key. The image of the key had been created by tracing an old key that had belonged to the grandmother of a CSE employee.

While the response to the challenge was enthusiastically taken up by some, ultimately a decision was made to go to the newly created Canadian Heraldic Authority (CHA) and Chief Herald of Canada Robert Watt and ask for their expertise in designing the badge. According to Chief Woolner, CSE “had ongoing discussions” with the Chief Herald before ultimately deciding on a final badge design.

The very first proposal had included much of what we have today: a blue circle representing the world of information, a gold bezant with a maple leaf symbolizing Canada, a pair of lightning flashes to denote communications, and a key representing the secure and sensitive nature of the information provided and protected by CSE. Atop it all was the Royal Crown, approved by the Queen for use in the badge.

This design, however, also included a large red maple leaf in the background, and field of small gold billets (rectangles) on top of the blue field. These were meant to represent “chips or bits of information,” and be symbolic of the complexity of the world of information. This design also included the motto, “UT ORATIO SIT LIBERA ET NUNTIUS SECURUS,” meaning “so that speech may be free and information secure.” This first design was proposed by Chief Herald Robert Watt, and drawn by artist David Farrar. It was officially presented by the Chief Herald to Chief Woolner on 24 September, 1993.

The design then underwent revisions, settling on a final design that included removing the larger maple leaf and the gold billets, and changing the motto to “NUNTIUM COMPARAT ET CUSTODIT,” meaning “To Provide and Protect Information.”

On 19 October, 1994, at a large all-staff gathering at the Federal Study Centre on Heron Road, the Chief Herald of Canada, on behalf of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, presented the Letters Patent for the CSE Badge to Chief Woolner. When asked in September 2019 about the event, Woolner said it was “a uniquely impressive and moving ceremony […] that gave to our employees a wonderful sense of pride and accomplishment.”

Almost two years later as part of CSE’s 50th anniversary celebration on 6 June, 1996, an official ceremony was held outside the Sir Leonard Tilley building (CSE’s past headquarters on Heron Road). There the pennant with the new CSE Badge was raised for the first time on a flagpole beneath the Canadian flag. According to Woolner in 2019: “I get a thrill to this day when I see our pennant displayed so prominently and flying so proudly, representing our organization and the thousands of men and women who worked in CBNRC/CSE and who have made such a contribution to the wellbeing of our country.”

How CSE got its badge (Part 1)

“Queen affirms importance of Canadian symbols” was the banner headline on a Government of Canada press release issued May 30th, 1988. In the release, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney and his Secretary of State, Lucien Bouchard, announced that on June 4th of that year His Royal Highness Prince Edward would present “Letters Patent” to Governor General Jeanne Sauvé, creating a Canadian office to grant coats-of-arms and generally advance the use of Canadian symbols.

In other words, Canada would be getting a Chief Herald, becoming the first Commonwealth nation to be empowered by the Queen to authorize official coats-of-arms. It didn’t take long for employees at CSE to take note of this change, as efforts had already been underway for almost a decade to have a unique crest created for the organization.

Earlier, in 1981, interest in creating a CSE badge can be found in an exchange of notes between the then-Director of U Group (SIGINT), Ron Ireland, and the Director General of Administration, Paul Gratton. Mr. Ireland had been investigating the possibility of adopting a CSE badge and had discussed it with officials at the Federal Identity Program (FIP) at Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS). At the time, Mr. Ireland concluded that TBS was unlikely to grant an exception to the FIP to allow for CSE to have and display its own badge. Further, TBS argued that “the effort could be inconsistent with, if not counter-productive to, [CSE’s] general objective of maintaining a low profile within the federal government.”

Nine years later in 1990, correspondence between Shane Roberts, a member of the Executive Staff at CSE, and a senior policy official at TBS about the possibility of developing a CSE Badge and an exemption to the FIP indicates ongoing resistance to the idea. TBS noted that it could not grant an exemption to the FIP without a letter of support directly from the Minister of Defence submitted to the Treasury Board (a Cabinet-level committee). Further, TBS indicates that it “would not appreciate” receiving such a letter as they felt it “could well raise questions as to what CSE is and does” that would warrant such an exemption.

The door wasn’t completely closed, however. Further discussion with TBS over the following year, including interventions by then-Chief Stewart Woolner, led to a compromise. An internal message written by Shane Roberts, dated September 6, 1990, indicates that TBS’ position was that “CSE may be entitled to have a special symbol which could be used on envelopes, in advertising or promotions, or on conference material and some other similar media, BUT it could not be used on letterhead.” Mr. Roberts adds that the distinction between these things is “a fine line […] but the high priests at TBS offer guidance on the distinction.”

The saga was not yet over, but after many years of effort the path was finally clear to CSE getting its own badge.